The year 2021 celebrates three decades of India’s economic reforms, as the Indian economy opened up its window to foreign investments. India, which for long, had adopted a model ala fabian socialism abandoned its near Soviet-style central economy, embracing liberalization, globalization and increased privatization. A traditional agrarian economy moved to enhanced privatization, as services industry grew in a new burgeoning India. The country, while prioritizing the growth of the services industry, skipped or rather not consolidating on the manufacturing component that made China the manufacturing capital of the world, as China adopted a farm to factory approach.

This paper seeks to highlight India’s value chain competitiveness and assess the emerging market’s economic potential viz-a-viz Thailand and Vietnam in Ease of Doing Business, Cost of Doing Business and Labor Market reforms. The goal is to identify areas of improvement and make specific recommendations to policy makers.

India’s potential to become a prominent manufacturing hub increased during the Covid-19 pandemic which, while causing a supply chain crisis across the world. As evinced during the pandemic, companies were seeking to buy “supply chain insurance,” as China, the ground zero for the origins of the virus and the major source of manufacturing, was impeded with lockdowns. Supply chain in China disrupted soon meant that supply chains around the world were disrupted. Hence, more and more companies are looking to diversify their supply chains. The pandemic provided an opportunity for new reforms and policies that sought to address supply chain issues and as building new resilient supply chains. The lack of robust supply chains impede the ease of doing business for international companies and the perceived reliability of the domestic value chain.

India has the potential to reap the benefits of multinational companies decamping production platforms from China, a country that currently has more than seven times the share of the global merchandise trade.

When shifting away from China to diversify the global value chains, multinational companies will analyze the competitiveness of India in comparison to Thailand and Vietnam with metrics including Ease of Doing Business (EODB), Labor Markets, and the Cost of Doing Business. India is already positioned uniquely as a country that has both a technically savvy and digitized workforce and young demographic, as the median age is 35 years or less, and hence has the human capital required for low-skilled and labor-intensive tasks.

The last five years have seen multiple business-friendly reforms that have enhanced the ease of doing business in India; this is in line with Prime Minister Modi’s Atmanirbhar Bharat (self-reliance) initiative. Indeed, global companies such as Siemens, Boeing, have set up manufacturing plants in India. However, it is imperative to make reforms in highly targeted policy areas, such as new business regulations, labor productivity, domestic reliability, and factory operation stability, in order to improve India’s performance and appeal to the international investment.

In addition to government policy reforms, the global companies will need to leverage government programs to leverage their own investment in India. The USISPF Hi-Tech Manufacturing in India Report estimates the hi-tech sectors have the potential of offering investments of US$21Billion that can leverage Atmanirbhar Bharat and other government reforms to create more than a million jobs over the next five years.

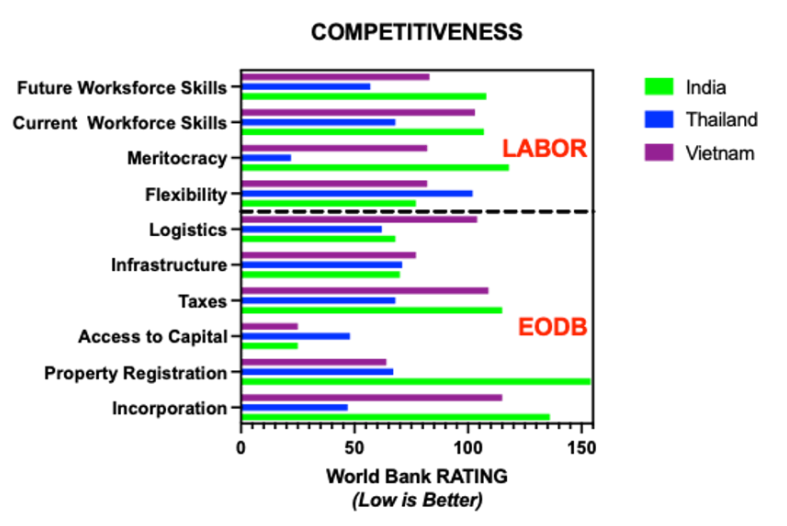

To ascend as a top manufacturing hub, India will have to compete with countries such as Thailand and Vietnam. USISPF conducted a study of India’s infrastructure and manufacturing competitiveness based on indexes from the World Economic Forum and the World Bank. India ranked 63, Thailand 21, and Vietnam 70 in the (Full Form) WB EODB 2020 that assessed 190 countries. The expanded report details the specific numbers and explanations of various parameters of comparison; numbers are summarized below in Figure 1. (Note: In the x-axis title, replace “rating” with “ranking”)

(EASE OF DOING BUSINESS GLOBAL RANKING)

Fig.1 Competitiveness framework based on World Bank Ease of Doing Business, 2020, for India, Thailand and Vietnam

Recommended Improvements in Ease of Doing Business (EODB) for Setting Up a Factory:

The ease of doing business is defined by the regulatory environment in terms of starting and operating a local firm.

State-of-affairs: India has steadily improved its global World Bank ranking from 142 in 2014 to 63rd in 2020 out of 190 countries. This is below Thailand and somewhat above Vietnam in the 2020 rankings. In terms of domestic comparison, large companies in urban and metro areas have the process eased by cooperation with local governments. For medium and small businesses, as well as more rural situations, the need for reform and regulatory consolidation is more dire.

The ground reality of setting up a factory in India, in terms of the days, cost, and land purchase, is very difficult. Not only is the number of approvals needed much higher than Thailand and Vietnam, the process is also more murky. Further, there is a large range from state to state. This could be sped up by establishing transparent procedures of registration processes for industrial activity and ownership.

simplifying the tax filing system overall can make the filing of tax more efficient. Enforcement of the Single-Window Clearance System wherein the industry interacts with a single one-stop regulator would reduce the bureaucratic issues with dealing with agencies at state and national levels. Improving the electricity regulatory environment and energy infrastructure by passing the Draft Electricity Act Amendment 2020 would allow MNCs and companies to formulate their investment plans judiciously. In addition, it is imperative to ensure the enforceability of contracts to enhance trust and confidence in India.

India has an abundance of labor, but productivity is an issue. By providing training to workers, sponsored and arranged by employers, differences in work methods can be alleviated. Flexibility in labor laws will accelerate the accommodation of new workers. The deliberate creation of Industrial Townships will make it easy to accommodate skilled labor. It has significant precedence in India through the ‘colony’ structure and is understandable in America due to the widespread use of this model during the early 20 century manufacturing boom.

Next, improving execution of the Infrastructure Project and prioritizing the political passage of an on-the-ground implementation of the National Logistics Policy will reduce cost of moving goods and improve connectivity. Dedicated freight corridors will optimize modal mix and continued impetus for a greater manufacturing and supply chain systems, including warehouses in the state policy framework will also develop the supplier ecosystem to enable free access to cost-efficient raw materials/components.

Despite the challenges, there is a lot of potential. Until now, India has missed many opportunities and there are many areas of improvement. Still, USISPF has an optimistic view of India’s competitiveness in the global manufacturing scene. Politicians like Amitabh Kant, from NITI Aayog, have explicit goals to compete with East Asian Tigers like Korea in high end manufacturing sectors, such as semiconductors. There will be at least 12 million new jobs in India. (More has to be said here)

With an envisioned target of a $5-trillion economy by 2024, and the projected potential for billions in investment and over a million in new jobs, reforms are necessary to stimulate India’s manufacturing sector. While progress has been made in the last five years through initiatives such as the labor code consolidation and lower corporate taxes, more focused work is needed to build the stability needed for foreign investment. A partnership of industry and government will allow India to leverage both low-cost labor as well as globally competitive trained engineers and operators; this in turn will allow India to be the key player in high-tech manufacturing. Investment and participation in global value chains will create the ecosystem for India’s international manufacturing leadership.