About US-India Strategic Partnership Forum

About USISPF

As the only independent not-for-profit institution dedicated to strengthening the U.S.-India partnership in Washington, D.C. and in New Delhi, USISPF is the trusted partner for businesses, non-profit organizations, the diaspora, and the governments of India and the United States.

Vision

The US-India Strategic Partnership Forum (USISPF) is committed to creating the most powerful partnership between the United States and India.

Mission

We build, enable, advocate, facilitate, and guide partnerships between the two countries by providing a platform for all stakeholders to come together in new ways that will create meaningful opportunities with the power to change the lives of citizens in both countries.

Author

This report was researched and written by Nisha Rajan, Senior Policy Coordinator at the US-India Strategic Partnership Forum.

Introduction

This report highlights the untapped potential of opportunities between the U.S. and India for increased bilateral trade and investment in the higher education sector. Focused cooperation through policy intervention would optimize commercial gains in the sector for both the partners.

The United States and India are important strategic and economic partners with common interests on multiple fronts. Currently, the U.S. is India’s biggest single-country export market, with a 16% share of India’s total goods and services exports in value terms, as well as India’s second-largest supplier of goods and services, with over 6% share. U.S.-India foreign direct investment (FDI) is relatively small, given the size of the two economies, but growing steadily. On the strategic side, defense trade is also on the upswing. Prime Minister Modi has implemented significant structural reforms over the past five years and generated hope for additional measures to open the economy further.

On the education front, international students brought $44 billion to the U.S. economy in 2019-20. The sector has been hard hit by the outbreak of Covid-19, exacerbating the existing challenges from immigration barriers that deter international students. It is important for both sides to discuss ways to ease U.S. immigration barriers, so the U.S. universities continue to attract Indian students.

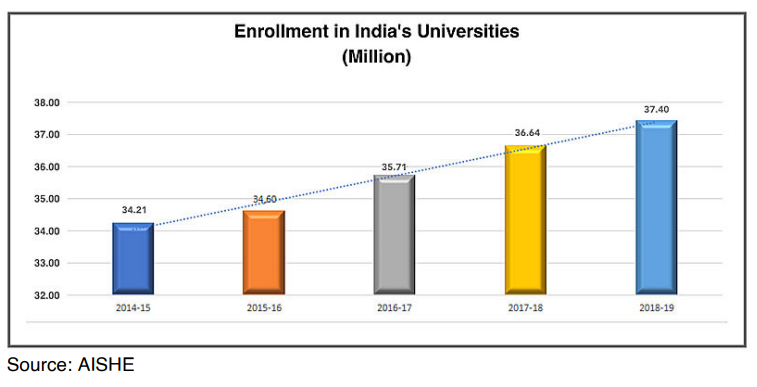

The Report explores these dynamics behind U.S.-India trade and investment cooperation in educational services and underscores opportunities for U.S. investors in India’s higher education services sector, which includes more than 37 million students. It concludes with specific recommendations for U.S. and Indian policymakers to overcome trade barriers and unlock tremendous potential for cooperation in the educational services space.

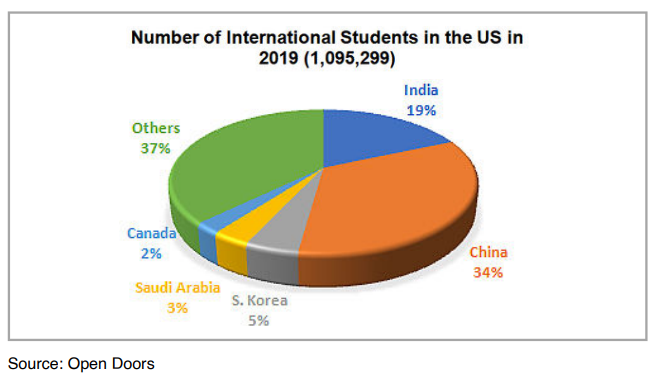

U.S.- India Trade in Educational Services

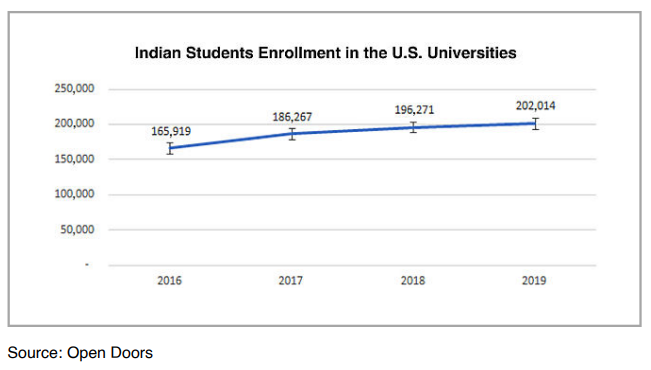

Trade in educational services is significant for both the U.S. and Indian economies. According to the 2019 Open Doors Report on International Educational Exchange, India is the second-highest country of origin for foreign students in the U.S. and has been, consecutively, for ten years. In 2018-19, before the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, more than 200,000 Indian students came to the U.S. to pursue undergraduate, graduate, non-degree, and optional practical training (OPT) programs, a 2.9% increase from 2017-18. The 2020 Open Doors report, recently released by the U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs and the Institute of International Education (IIE) highlights that during the 2019-20 academic year, India remained the second largest source of international students in the U.S., despite a 4% decline to 193,124 students, making up 18% of the total higher education international student community in the U.S.

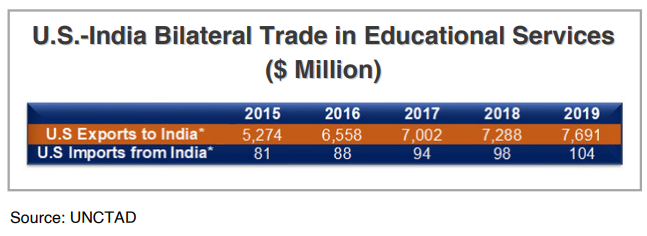

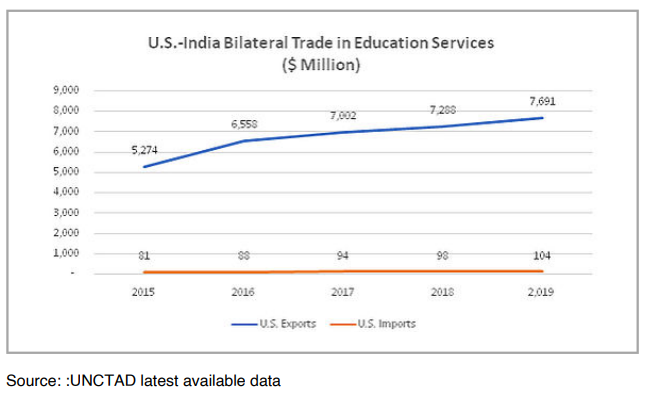

The pre-pandemic trend was also evident in the bilateral trade statistics, which capture spending on educational travel between the two countries. From 2015 to 2019, the amount spent by Indian students on educational travel to the U.S. rose by 45%, to nearly $7.7 billion. Significantly, these trade data only include cross-border expenditures and do not reflect the additional economic activity generated by students through local spending on fees, housing, and living expenses.

The outbreak of COVID-19 had a major impact on international student enrollment in the U.S. for 2020. Border closures and movement restrictions forced a significant drop in international enrollments in the U.S., including from India, last year. Nearly 90% of the 599 schools surveyed by the Institute of International Education (IIE) expected international student enrollment to drop in Fall 2020, with 30% anticipating a substantial decline. Additionally, 70% of schools expected some of their international students would not be able to travel back to the U.S. in the fall.

Educational Services Trade Barriers

There are four primary modes through which educational services are imported and exported between countries: Mode 1, involving cross-border services transmitted through infrastructure, such as distance learning; Mode 2, representing direct consumption abroad, as when a student attends university in another country; Mode 3, through a commercial presence, such as the education provided within a country by a locally established affiliate of a foreign-owned and controlled University; and Mode 4, though the movement of natural persons, such as a foreign national hired in a country to provide educational services as an independent contractor or employee.

In the context of education services trade between India and the U.S., the largest constituent is Mode 2, representing the large number of Indian students studying in the U.S., plus their spending on educational fees and related costs of their stay. Education services imports also involve Mode 3, with U.S. universities operating international campuses and giving foreign degrees in India, though these imports are limited by India’s lack of a fully implemented regulatory framework for opening foreign universities.

In general, the most common barriers to the provision of cross-border educational services are in Modes 2 and 3 and involve restrictions on travel abroad based on discipline or area of study, visa and entry restrictions, and restriction on basis of quota for countries and disciplines.

U.S. education service providers are globally competitive but have traditionally faced significant market access barriers in India, such as limits on foreign ownership of campuses and joint venture requirements. These restrictions should ease over time as India implements its New Education Policy (NEP) 2020, approved on July 29, 2020, which includes reform measures intended to facilitate establishment of foreign university campuses in India.

On the other side, Indian students wishing to study in the U.S. also face barriers, primarily through visa and entry restrictions, while the COVID-19 pandemic has created additional challenges for foreign students at U.S. universities. Current U.S. F-1 student visa regulations allow students to take only one class online per semester. Hence, the shift to online instruction in Fall 2020 became problematic for Indian and other international students who study here but had to remain outside the U.S. for months due to the pandemic crisis. For Spring 2020, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) allowed students to finish classes online if the entire university switched to online instruction, but legal and regulatory changes may be required to continue such an arrangement beyond the current academic year.

The pandemic may serve to perpetuate Mode 2 barriers in the U.S., not least because unprecedented levels of U.S. unemployment have eroded support for immigration generally. While most of the jobs lost to the pandemic have been in the services and retail sectors, creeping losses in professional services, STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics), and other tech fields could lead to more restrictions on H1B, OPT, and graduate student visas. USISPF members believe such a development could be a significant deterrent to India’s integration in the global system overall.

On the other hand, the COVID-19 pandemic may give impetus to reduce Mode 3 barriers in India, as domestic students may prefer to enroll in foreign Universities in India universities due to safety concerns. The impact of depreciating currency must also be noted, as the devaluation of the Indian rupee against the U.S. dollar may make the U.S. education unaffordable for many students.

While Mode 4 education services (Indian teachers going to the U.S. to teach) are not significant to the overall total of trade, Mode 1 (distance and e-learning) is expected to have a significant growth in future as India expands its base of Internet users and the U.S. continues to be a global provider of e-courses.

Evolving U.S. Anti-Immigration/Immigration Position

The most recent pre-pandemic data by Graduate Management Admission Council (GMAC), released in September 2019, estimated that just 45% of Indian students who took the GMAT applied for admissions in the U.S. Business Schools in 2019, down from 57% for courses that started in 2015. This decline was mostly due to the dimming prospects from increasingly stringent H1B visa regulations.

Foreign students are a major source of revenue for U.S. universities, and Indian students make up a significant portion of the total international student community in the U.S. However, the restrictive immigration laws in the U.S. have proved to be an effective trade barrier, hobbling the growth prospects of its $44 billion higher education market. In these circumstances, the trade gets diverted as international students opt for alternative markets, such as Canada, Europe, Singapore, New Zealand, and Australia.

According to the ‘Early Warning Signals Report’ by GMAC, anti-immigration rhetoric in the U.S. also impacted its higher education market. A 2018 survey by GMAC found that 44% of Indian candidates agreed fear for their safety and security would prevent them from pursuing U.S. degree. Creating barriers to mobility such as the current imbalance in supply versus demand of U.S. educational visas effectively restricts innovation, opportunity, and economic growth. According to the 2020 GMC Application Trend Survey Report, international candidates were less likely to commit to enrollment and more likely to ask for deferrals in 2020 due to the continuing pandemic situation. The pandemic-driven uncertainty impacted the decisions of 57% US business-schools who responded by extending deadlines and deferral policies; as a result, the number of total applications increased, albeit there was a 34% decline in international applications compared with that in 2019.

The 2020-21 academic year will likely reflect impacts of the pandemic, but the Biden Administration is likely to have a favorable bearing on the number of international students, including from India.

A poll conducted by the GMAC suggests that international candidates would be more likely to study in the United States with Biden as president. Biden administration’s immigration policies, reportedly, propose to rationalize employment-based visas, increasing the overall number of such visas, with no cap on graduates of PhD in STEM.

The Biden Administration has also pledged to streamline and improve the naturalization process for qualified green card holders, and, believes that foreign graduates of a US doctoral program should be given a green card with their degree.

On the immigration side, the Biden Administration is expected to welcome family-based legal immigration, encouraging diversity in the United States. President Biden has not spoken extensively about the international education and high-skilled immigration specifically, but his administration has already proposed legislative action to bring immigration reforms supporting Obama-era policies, which were more welcoming for international students than in those under the Trump Administration.

Foreign Students – Major Source of Revenues for the U.S. Universities

The U.S. has remained a major supplier of higher education to India. The U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs has accorded top priority to promoting international student mobility, as this is the biggest source of education services exports. When education services are supplied by the U.S., as an importing country, India sends money into the U.S. through students’ expenditure for enrollment fees, books, accommodations, and other living expenses. This export has a multiplier effect on the local economy in the form of students’ spending and their engagement with U.S. businesses.

The cost of education at U.S. universities is relatively higher than that in Europe or other Asian countries, generally with no discounts, and visa requirements often necessitate a financial guarantee. The different tuition and fee structure for American and international students at public universities reportedly ratio of 1:3-effectively results in discounted rates of higher education for American students. Given the huge state budget shortfalls predicted this year due to the pandemic and reports that 30% of American students plan to delay enrollment, foreign students will become even more critical for U.S. universities.

STEM-pool Contribution in the U.S. Economy

Indian students who study at overseas universities typically prefer not to return to India immediately after completing their degrees. The U.S. OPT program provides students particularly from the STEM field – with reasonable time and opportunity for professional training. The OPT program has also proved very helpful for U.S. companies, given the imbalance of demand to supply of skilled STEM workers. According to the GMAC Report, the OPT-STEM program has increased economic activity and has even kept some smaller companies from going out of business entirely.

With the recent reduction in enrollment of foreign students in U.S. universities, the U.S. economy risks witnessing cascading effects given the important role these students play, brining tech skills and STEM knowledge that stimulate innovation, increase competition, and create jobs. According to a 2017 report by the National Foundation for American Policy, in approximately 90% of U.S. universities, a majority of the full-time graduate students in Computer Science and Electrical Engineering is international students. The trend seems to continue; according to the Open Doors Report 2020, over half (52%) of international students in the U.S. universities pursued majors in STEM fields of study (engineering, math and computer science, physical and life sciences, health professions, and agriculture) in 2019-2020. Some U.S. national security experts have raised concerns about the possibility of theft by foreign students of intellectual property and latest research; however, Indian engineers and scientists have contributed substantially in the U.S. for decades – in the corporate sector and through joint research programs – earning the trust of U.S. business and Government agencies.

According to the Smithsonian Science Education Center’s estimates, as of 2018, there were approximately 2.4 million unfilled high-paying STEM jobs in the United States. Filling these jobs could make the U.S. more globally competitive and contribute substantially to economic growth.

The Open Doors data quotes U.S. Department of Commerce estimates that international students contributed $44 billion to the U.S. economy in 2019, a decrease of 1.5% from the previous year due to the pandemic impact. According to the latest data from NAFSA: Association of International Educators, the more than one million foreign students in the U.S. contributed $41 billion and supported more than 458,200 jobs during the 2018-19 academic year; however, the 2019-2020 academic year recorded an unprecedented drop of 5% in foreign students’ contributions supported by 415,996 jobs, reflecting clearly the impact of COVID-19 on the economic contributions of international students.

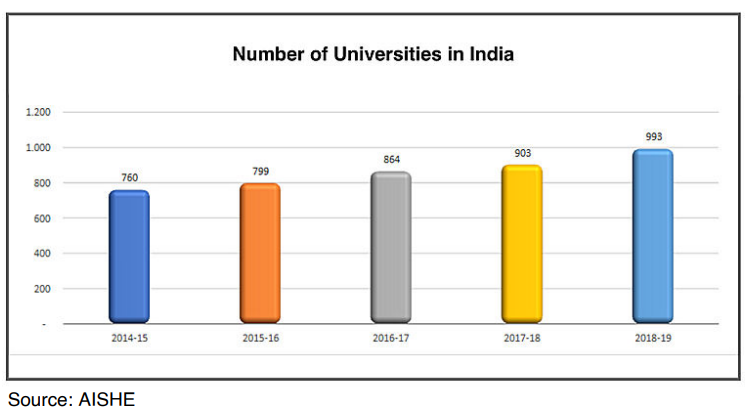

Investment Cooperation – Establishing Foreign University Campuses in India

India’s education services market presents tremendous investment opportunities for U.S. universities. As per the All India Survey of Higher Education (AISHE), India has one of the largest education systems in the world, with more than 260 million students enrolled in 1.52 million schools, and 37.4 million higher education students in over 993 universities and more than 50,000 higher education institutes. As per the QS Higher Education System Strength Rankings 2020, India’s tech schools – such as IIT Bombay, IIT Madras, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore and IIT Kharagpur are in the top 200 global universities, offering competitive courses and degrees in terms of quality, at a much cheaper cost compared to the U.S., the U.K., and other developed countries. India Brand Equity Foundation (IBEF) estimates the market size of the higher education sector in India will be more than $35 billion by FY 2025. India also offers a large market for e-learning, which is expected to reach $1.96 billion by 2021 with around 9.5 million users, according to the IBEF.

According to the IBEF research, current trends point to the growing demand for education in India, leading to a lucrative $180 billion market by FY2020. In a bid to become a regional hub of quality higher education, India has been making efforts to improve its domestic higher education soft and hard infrastructure. U.S. universities have shown tremendous interest in establishing campuses in India. The recent approval of the NEP 2020 by the Indian cabinet is a significant step towards harmonizing the Indian higher education system with the international standards.

USISPF members applaud the initiative of the Modi Government to undertake the needed reforms to facilitate foreign investment in the education infrastructure of the country. The Government of India will now need to swiftly implement policies to facilitate establishment of foreign university campuses, so that the international level of education in India can meaningfully contribute to its economic growth in a sustainable manner.

National Education Policy 2020

India approved The National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 in July 2020, to be fully implemented in phases by 2040, proposing a simplified regulatory structure for the education sector. The policy entails a reformed roadmap for higher education, doing away with the current college affiliation to universities system through conversion into autonomous and independent higher education institutions (HEI) which will be free to decide to undertake research and teaching activities per its abilities. Other provisions include launch of a four-year bachelor’s degree, opening India to foreign universities, incorporating vocational education in college curriculum and creation of a National Research Foundation. India will enact these changes through the Higher Education Commission of India (HECI) legislation. The HECI law is expected to accommodate foreign institutions in a flexible manner. At present, the policy envisages allowing only the top 100 institutions globally to open campuses in India but depending on the response of these top 100 institutions, India may open the door to other foreign institutions.

USISPF Recommendations

For the U.S. Government

- Encourage comprehensive immigration reforms that allow robust student mobility by reviewing and streamlining the student visa process, especially for countries that send the most students to the United States.

- Enabling framework for OPT (Optional Practical Training) Expand training opportunities for capable international students following graduation.

- Create a coherent national framework for international education that aligns with the U.S. diplomatic, economic and immigration goals.

- Increase immigration numbers to the levels during the Obama administration.

For the Government of India

- Adopting global standards for testing and admissions purposes – exams, such as TOEFL® and GRE®, that are commonly used for admissions to universities in the U.K., the U.S., and Australia may help Indian universities attract more qualified students from across the region and around the world and elevate the status of Study in India program.

- Adopting English language assessments such as TOEFL and TOEIC that are aligned to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) for graduation purposes may also help to elevate the employability of graduates of Indian universities on the global economic stage and help India to achieve better investment attractiveness, bolster the economy, and increase its workforce export numbers.

- To harness the potential of e-learning, India may need to change the regulatory structure to accept credentials earned at the U.S. universities online at par with that earned by studying physically in the U.S.

India has already approved major policy changes to allow the establishment of foreign campuses in India. USISPF specifically emphasizes:

- Prioritization of full implementation, albeit in phases, of the new National Education Policy 2020.

- Clarity and transparency in implementing policies that may create the potential for double taxation for foreign suppliers that are interested in establishing a presence.

- Implementation of facilitation in repatriating salaries and income from research in respect of foreign suppliers.

- Foster and encourage ecosystems in Higher Education Institutions for high order internationalization.

- Better coordination among Center and States for implementation of the NEP

Conclusion

Removing trade barriers on the free flow of students and educational services can strengthen the competitiveness of the U.S. economy by way of value addition and job creation.

USISPF visualizes tremendous opportunities for U.S. and India in the higher education segment from both trade and investment perspectives, which are crucial for the economic growth of both economies. There are mutual gains for both partners, as the U.S. wants to improve its bilateral trade balance with India to save jobs through increased exports, and India’s young STEM talent assesses the U.S. as one of the best destinations for world-class higher education and professional training opportunities. If visa barriers are addressed, the bilateral trade in education services could record exponential growth.

India’s increasing contributions in the U.S. economy as the second-highest importer of U.S. education services should not go unnoticed in the bilateral trade discussions. Given the present dynamics of trade in educational services between the U.S. and India, trade cooperation in this area will be icing on the cake. Likewise, India should take a proactive approach to start implementation of the NEP 2020 to address investment barriers, as boosting investments for developing its higher education sector will help India become a more competitive destination for a world-class education.

Points For Reflection

USISPF underscores a few questions/points to ponder and reflect in policy formulation, should the two governments decide to take forward the cooperation in Higher Education:

For the U.S. Government

Visa and Migration Issues

- Can there be a single window clearance for students and academics for entry visa?

- Are the visa and migration rules for inbound students clear, transparent and consistent?

For the Government of India

Openness

- Does India have a national strategy for Internationalization of Higher Education (student mobility, academic collaborations, development goals)?

- Is there a need for a dedicated body for Internationalization of Higher Education at the national level?

Regulatory Environment for Institutions

- Can there be a legislation to facilitate entry of quality foreign higher education institutions?

- Do we have facilitatory mechanisms for cross-border programs by foreign education providers?

- Can there be a differential fee structure for foreign students?

- Can we allow for greater institutional autonomy to allow for better institutional collaboration on internationalization of higher education?

Quality Assurance and Degree Recognition

- Can we have quality assurance agencies to advise, monitor, accredit cross border activities of domestic institutions and foreign institutions?

- Do we have an institutional mechanism to recognize foreign qualifications in a clear, transparent and consistent manner?

Access and Equity

- Is there financial support offered by institutions/government for inbound and outbound students to pursue higher studies?

- Are these well publicized and do we have transparent and needs blind approach for these financial aid initiatives?